The Babel 3.0

(2015 - 2017)

On BIBLE 0.3

In an attempt to imply the manners and investigate the idiosyncrasies state authorities tend to use in order to present themselves in the public space, the Babel Fragments project used the internet as a research field in order to find information regarding parliamentary structures worldwide.

The resulting archival collection of images and information is connected with the biblical story as in this context, the parliamentary buildings of 184 different countries are perceived as glorified fragments of the mythical tower, which now serve as national symbols of authority. By becoming flags, symbols of differentiation from the Other, the buildings that are meant to establish discourse as a civil conquest, become shrines of the Peoples’ failure to communicate. In a sense, through their oxymoronic condition, they are completing the mission of the Tower’s destruction.

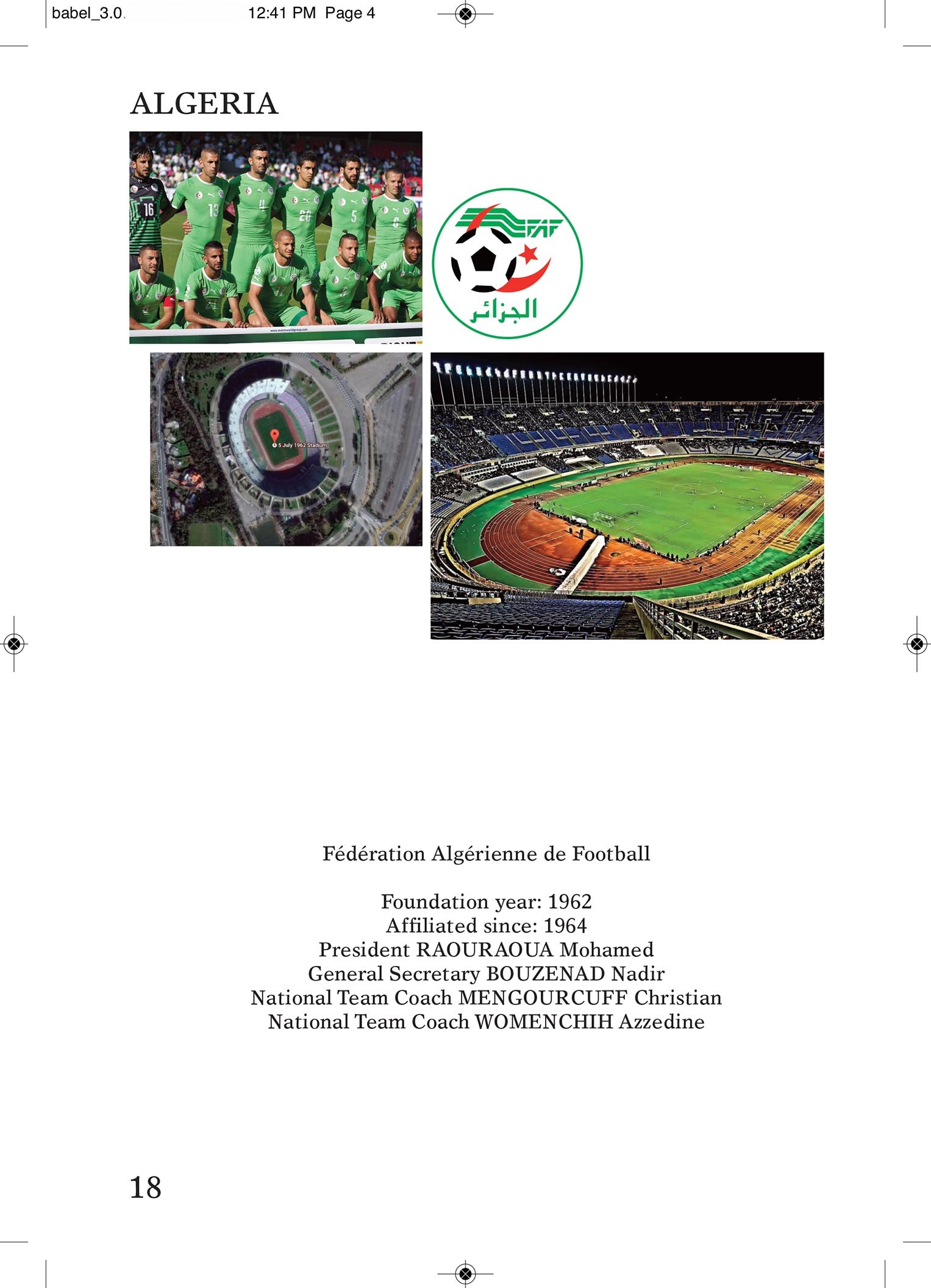

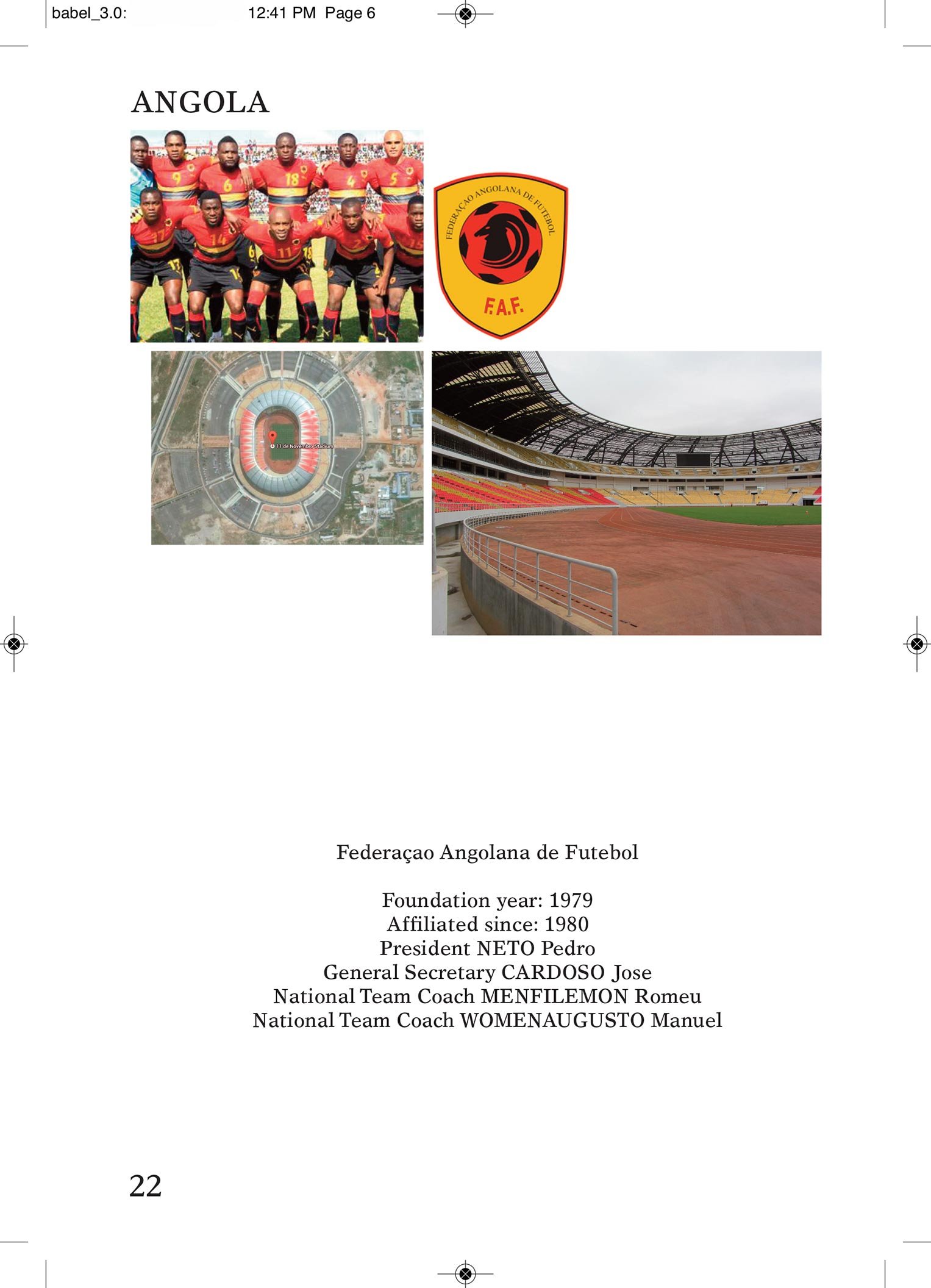

In discussion with the aforementioned project, Vassilis Vlastaras creates an archive of all the stadiums around the globe that host the national football teams associated with FIFA by the time of the project’s completion (May 2018). Reflecting the iconography of Babel, Vlastaras presents a collection of data that oozes vanity and banal nationalism: Colorful and luxurious gigantic structures, jerseys, flags, male role models etc. In an archive such as this, where all that is displayed is presented on an equal scale, we are pushed to discover the irregularities, the elements that actually differentiate one from the other.

Issues such as race, financial dominance and living conditions make their appearance in the pages presented, even though they are somehow camouflaged by the exuberant confidence and magnanimity of the iconography.

The initiative undertaken by Vlastaras creates a strong parallel to the presumptuous promises that are dominant in the narrative of large-scale athletic endeavours such as the world cup; where every country appears to partake in an equal opportunity competition, where everyone seems to have the same starting point. But as performance excellence is derived from a multitude of factors, spanning from political priorities to socioeconomic conditions, the fact that both style and level of performance are mainly attributed to cultural elements, generates a vicious circle of identity attribution and appropriation. Therefore, sports, and team sports in particular, become a platform where identity stereotypes flourish, since we tend to perceive the way national teams function on the field as a mirroring of our assumptions in regards to the identities of the country each team represents: Germany is cruel and methodical, Brazil is flamboyant, Greece is scrappy and spirited, while Nigeria is talented, strong but undisciplined. The issue with such assumptions is that they reproduce a vague understanding of cultural elements, while they live out of the equation real-life conditions that determine athletic excellence. As a result, a squad’s potential success is attributed to cultural -if not racial- superiority.

In conclusion, it would be important to point out that alongside the aforementioned elements, through this archive, we are becoming witnesses of the urge that drives nation-states to demonstrate power, sovereignty and legitimacy through many media, including the ambience of Athletic structures. Even if stadiums are supposed to be built in order to host and contain an in-house audience, in the context suggested by Vlastaras, another function becomes apparent: The fact that these stadiums, alongside the teams they host, are means for a state to demonstrate itself as an equal and powerful member of the world stage.

Alexis Fidetzis